At HM Payson, we are used to fielding questions about the stocks, or the approaches, of the moment. While we are firmly committed to quality companies and a long-term approach, our Portfolio Managers do follow unusual equity activity, aiming to bring insight to any questions our clients might have. Things like: What are the dynamics at play? What are the fundamentals? Is this trend big enough to impact my portfolio? And most recently… What exactly happened with GameStop?

A full explanation of the GameStop scenario starts with a brief recap of the history of the internet. It moves fast — and that is, in many ways, the important takeaway.

As we approach the one-year anniversary of the Covid-19 pandemic, it’s hard to imagine what this year would have looked like without virtual connection. And yet, 30 years ago today, not only did we not have videoconferencing, but the world’s first web page had yet to be published.

That milestone happened in August 1991, kicking off the first internet era. Early-adopting companies began to dip their toes in the water, creating (with the help of expensive in-office server equipment and a Web Master) static web presences analogous to digital brochures. You might remember those first ten years of “the information superhighway,” and long-term Payson clients might even remember this (c. 2000):

All of this was, for the most part, a benign and controlled situation. During that time, any widespread threats the internet posed to commerce or the markets were swiftly addressed by online security experts behind the curtain; and eventually, for the most part, accounted for by regulators.

It was only in the early 2000s – at the dawning of what was then called “Web 2.0,” that it became easy for any member of the public to publish content online. And with that shift, everything changed. Web 2.0 brought back and forth conversations to the “web surfing” experience – first via chat rooms, then instant messaging, and blogs with comments. Websites weren’t just documents to read, they were places to participate.

Facebook emerged in 2004, and other social media platforms followed. Since then, social networking has changed our lives in many ways – some for the better, some for the worse. But most notably for the purpose of this discussion, it has sped up the pace of change and has made it easy for people with the rarest of interests or the craziest of ideas to connect with like minds.

In 2012, a young consultant named Jamie Rogozinski was frustrated by traditional buy and hold investment advice. He wanted a place to laugh, swear, and commiserate about stock trades gone both good and bad. So, he joined Reddit and started a forum called WallStreetBets (WSB).

Nothing much happened on his forum until 2019, when the commission-free electronic brokerage firm Robinhood emerged. Robinhood goaded everyone else in the online brokerage world into eliminating commissions, and subsequently small investors flooded into the markets, typically investing between $1,000 and $5,000. For investing tips, many of them joined WSB.

By the beginning of 2020, WSB had amassed 500,000 followers. In the horrific COVID-precipitated March and April declines, many of them bought with what they felt they could lose. Locked down at home, everyone had more time to spend in front of screens. They exhorted each other to be brave, to have strong hands, and remember YOLO (you only live once). As the markets recovered, they became bolder and more profane. At year end, they were a million strong. That was when someone on the forum noticed something about a beaten down video game retailer called GameStop (GME).

GameStop sells video game CDs from physical locations, in a world where such purchases are increasingly downloaded from or played directly on the internet. Their business model is eerily reminiscent of Blockbuster Video, which filed for bankruptcy in 2010 (and made a fortune for short sellers). Many professional investors remembered this, and established “short positions” in GameStop shares, anticipating the company’s inevitable demise.

Just as you can buy shares in a company when the price is low and realize a gain when it goes up, you can also do the opposite – you can sell shares you do not own, by delivering borrowed shares to the buyer. (The art of borrowing said shares or “stock loan” is a major source of revenue for most brokerage firms). You hope to buy the shares back, and replace the borrowed shares, at a lower price. But things can go very wrong. If the shorted stock instead increases in value, it becomes not only a loss but a loss in an ever-larger position. If the price continues to rise, the brokerage that effected the transaction will call for increased collateral, usually daily. If the collateral is not delivered in a timely fashion, the brokerage firm can initiate a buy-in of the stock to protect their own capital position.

This is where the WSB cabal saw opportunity. They recognized that an astounding amount of GameStop shares had been sold short, by some accounts more than the entire number of shares outstanding. By acting in concert, they felt they could drive up the price of GameStop enough to force the short sellers (or their brokers) to have to buy to stop their losses. This technique is known as a “short squeeze.”

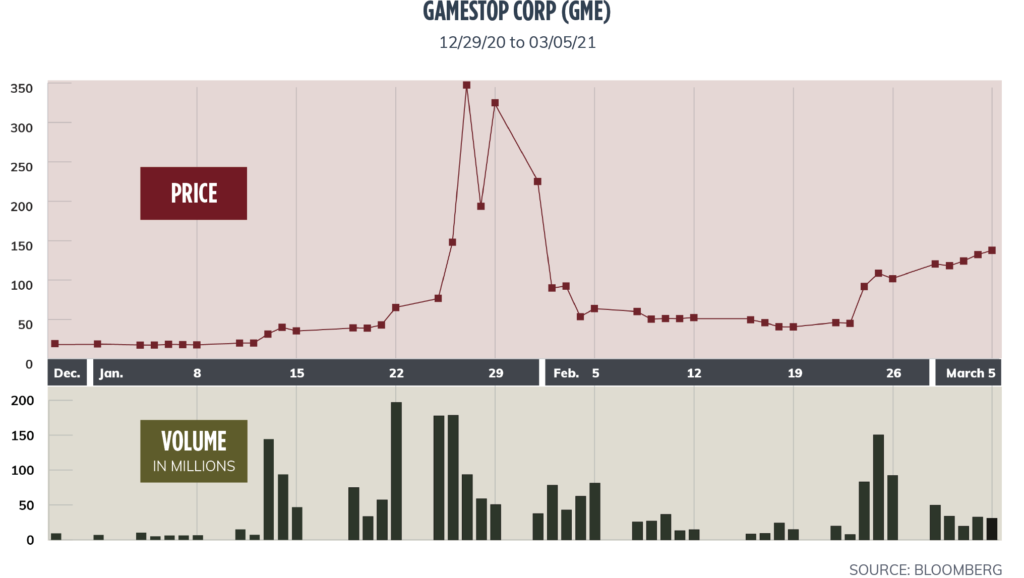

They turned out to be right, in spectacular fashion. On Jan. 12, GME closed at $19.95 on only 7 million shares traded. The next day, it closed at $31.40 on volume of 144 million shares. Over the next week and a half, the share price (and Reddit WSB membership) marched steadily higher. On Jan. 22, GME closed at $65 on 197 million shares.

Short sellers seemed to be covering, and the WSB crowd smelled blood. That weekend, the Wall Street Journal reported on the “David versus Goliath” drama. On Monday, GME opened at $96.73 and ran to a high of $159 before reversing course and closing at $76. Typically, this sort of dramatic gap up and reversal would have been the top of the move.

The WSB-Robinhood axis had other ideas, however. By Thursday, Jan. 28, they had managed to push GME shares to an intra-day high of $483, producing multi-billion dollar calls for collateral against many of the largest institutional trading firms (read: hedge funds), and making millions for the little guys who bought in just days before. One prominent short seller shut down for good. Predictably, the media was in a frenzy just as GME began its inevitable retreat. The hysteria unnerved the broad market; the S&P 500 closed off 3.5% for the week.

There are now thought to be two million Reddit WSB members, and together they can move the prices of target companies at will. (After taking a few weeks off, “the pack” returned to GME at the end of February and drove the price from $45 up to $170 in two days). While it is illegal to “act as a group” to influence stock prices, WallStreetBets maintains it is simply an investment chat room, without any of the organizational structure of a group. After reading some of the wild posts of their members, many would agree.

We believe they are in essence a digital wolfpack, acting in concert when on the hunt, but with individual agendas as well. Congress and the securities regulators are currently scrambling to catch up and make sense of the situation. One thing is clear: a fundamentally different force has unexpectedly emerged upon the financial landscape, and it is not going away without a change in regulation or law. And the dangerous occupation of short selling has become more dangerous indeed!

For HM Payson clients, the chaos described above had no repercussions. As an investor in high quality domestic companies, our firm tends to gravitate to very large businesses with hundreds of millions of shares outstanding. Apart from low-basis inherited positions, we have minimal exposure to the smaller capitalization issues that can be mauled by WSB and their ilk. Additionally, as a “long-only” manager, we do not sell short. And so, the only effect upon your portfolios would be exposure to a general market decline like that of late January, and this would be (and was) temporary in nature. Still, the investor chat room phenomenon bears watching, if for no other reason than the fact that its membership and assets continue to grow.