Saving and investing are the keys to financial security – taking the financial anxiety out of unexpected emergencies and paving the way to a comfortable retirement. Still, many Americans reach their 30s and 40s without a clear saving and investing plan. Fortunately, there is time to take action.

It starts with setting a saving process into motion – this is the top priority. Then you can put your accumulated funds to work with proper investment.

Your budget should include line items for saving toward three main goals:

Emergencies and Large Expenses – The amount you set aside each month for each goal depends on the total cost and the time horizon (how much time there is until you’ll need the funds). An emergency fund has a short time horizon (you might need funds next month for a car repair), so you’ll want to meet this goal first. Once you have accumulated cash equal to three to six months of expenses for your emergency fund, you can work towards saving for an upcoming large purchase, such as a down payment for a home.

Retirement – Gone are the days of most employer pension plans, so it’s almost always up to the individual to save for retirement. And the sooner you start, the less you’ll have to save each year, as your money will have more time to compound. We advise individuals to start by saving at least 10% of their gross pay for retirement, gradually increasing that rate to 15% or 20% over time. If your company has a retirement plan, you can automate this through a payroll deduction. As Warren Buffet once said, “do not save what is left after spending; instead, spend what is left after saving.”

Education – With emergency funds in place and retirement savings on track, you can turn your attention to saving for your children’s education. We advise making education savings a lower priority than retirement, as there are many ways to finance education but very few ways to finance retirement.

Although there are three distinct savings goals, we do not recommend saving exclusively for one at a time; rather, the idea is to prioritize your goals, but still save for them all in tandem.

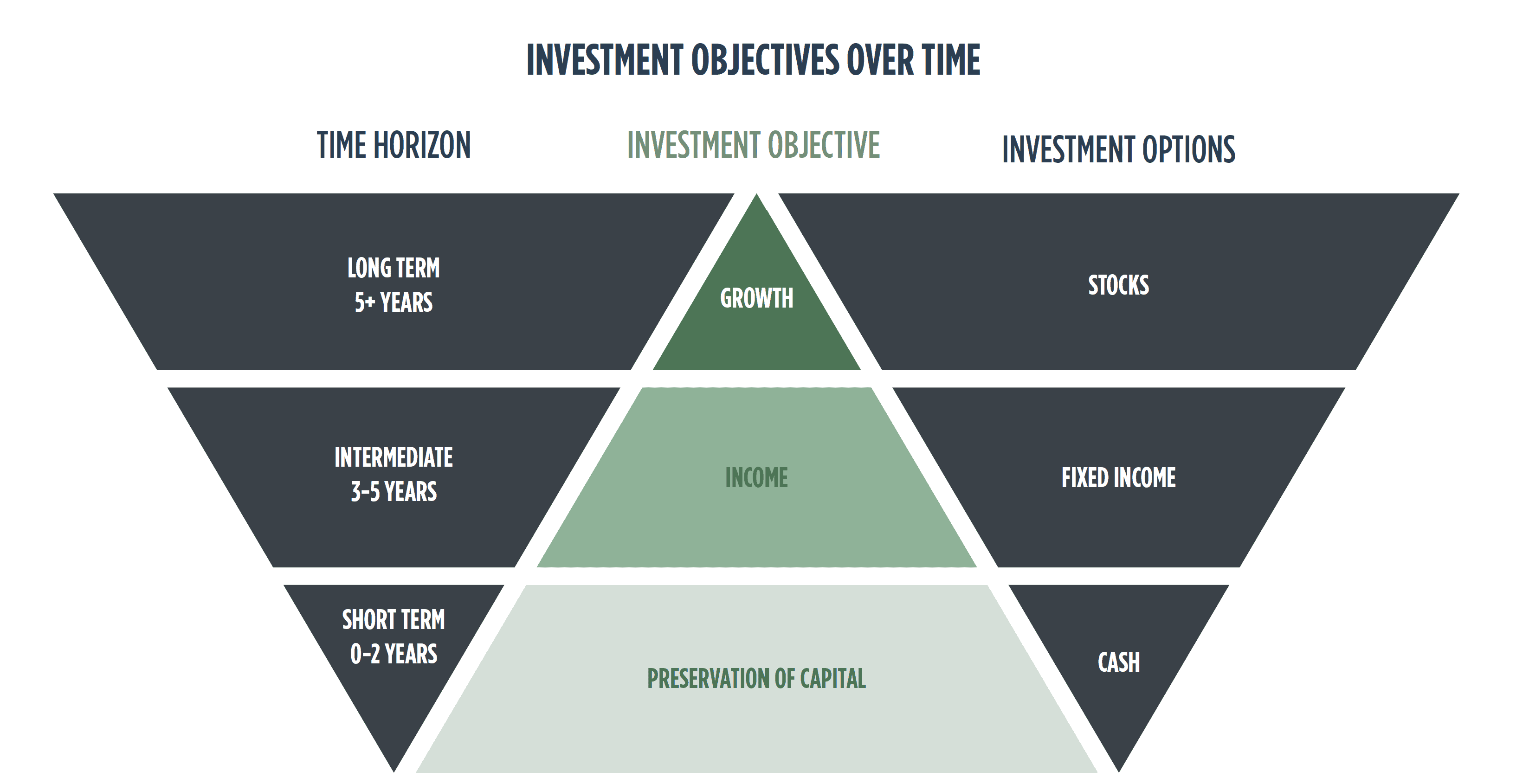

How you invest your money (stocks vs. bonds) will depend on your investment objective – which, in turn, depends on your time horizon.

The chart below depicts the relationship between time horizon, investment objective, and investment options. If the time horizon is long (5+ years), as it typically is with retirement, then the investment objective should be growth, which means you’ll invest funds in stocks. If time horizon is intermediate (3-5 years), then the investment objective is income, so funds should be invested in fixed income (bonds). If the time horizon is short (0-2 years), as with an emergency fund, then the investment objective is preservation of capital and the funds should be invested in cash.

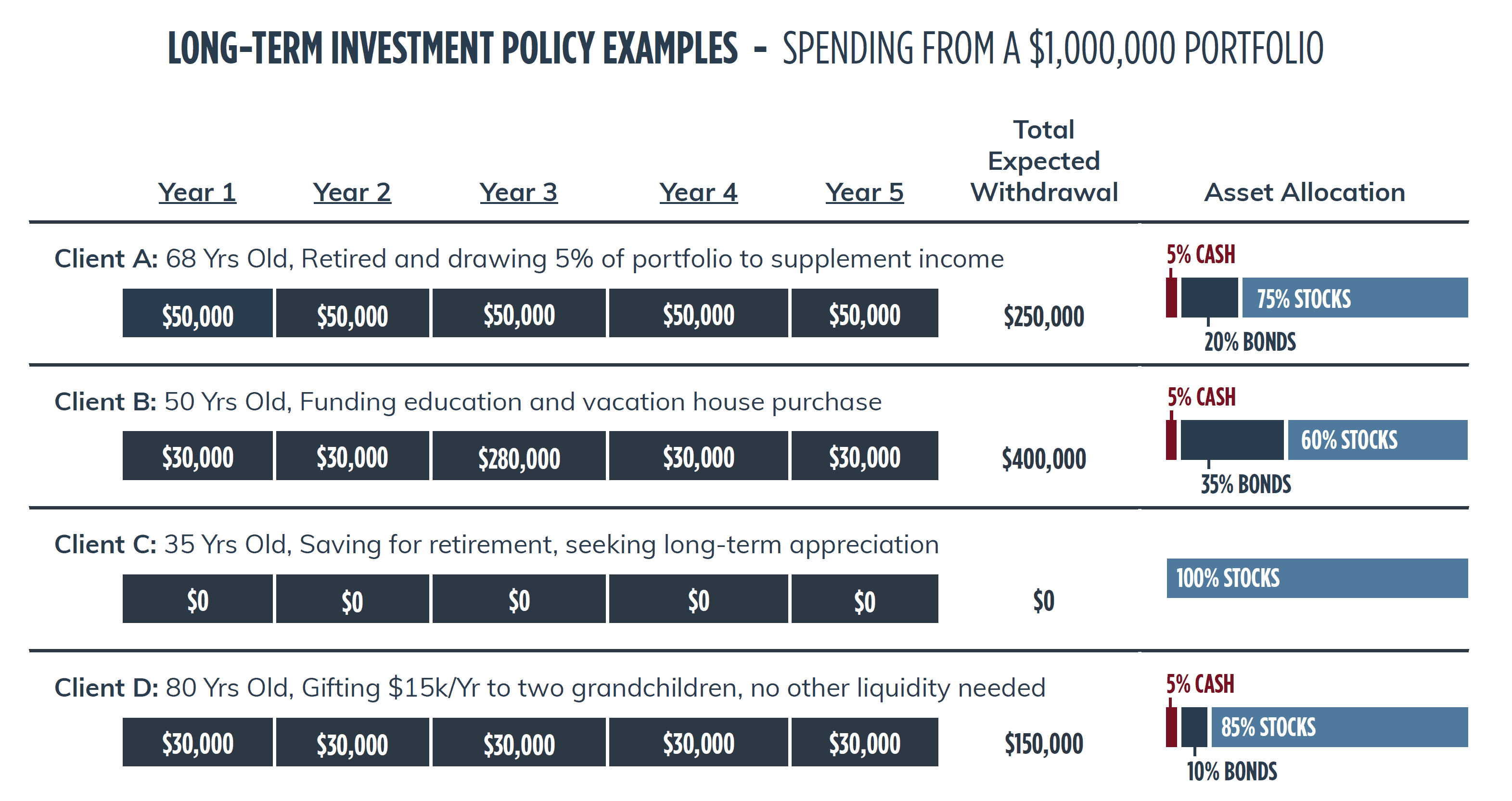

Asset allocation refers to the different percentages that should be invested in each asset class (stocks, bonds, and cash). To determine your ideal asset allocation, first use your investment goals to identify your time horizon, then match the appropriate investment assets to those goals. While there are no guarantees when investing in equities, five years should be enough time to mitigate short-term volatility risk, as good years in the market offset bad years. As evidenced by the examples below, asset-liability matching makes it much more likely that you will only need to worry about the risks you can control.

68-Year-Old Retiree

Below is a simple example of a recently retired 68-year-old investor with a $1 million portfolio who needs to spend 5% of their portfolio each year for living expenses, increasing annually for inflation. Cash and short-term bonds cover spending in years 1-5, and stocks cover their long-term spending needs 5 years and beyond. The result is a portfolio approximately 75% in stocks, with 25% split between bonds and cash. Most of the retiree’s spending occurs beyond the fifth year, so it’s important to use stocks to hedge against inflation risk. This results in a larger weighting to stocks compared to bonds.

Over time, the portfolio will need to be rebalanced by selling stocks to replenish the bond and cash positions. Because the investor has five years of fully funded spending, the rebalancing can be done in times of market strength and avoided during times of market distress.

35-Year-Old Investor

Conversely, consider a 35-year-old who is saving for retirement and does not need to spend any cash from their retirement portfolio for 30 years. Using the same asset-liability matching framework, they have no practical reason to allocate any of their retirement account to preservation-type assets, as long-term inflation is a larger risk than short-term volatility, so we would want to allocate 90% to 100% of the account to stocks.

Each asset class offers a different degree of risk and return. Stocks are designed for long-term growth, but offer little short-term certainty. Bonds (also referred to as fixed income) produce more income than cash; but unlike stocks, they are not designed for long-term growth. Cash and equivalents (e.g., money markets) offer short-term certainty, but no growth; and therefore, little protection against long-term inflation risks.

Each major asset class includes a myriad of sub-asset classes.

Stock subclasses include:

Bond subclasses include:

By diversifying across sub-asset classes, you can potentially add to your returns while reducing volatility. That said, any additional yield offered by debt instruments (such as high yield bonds) increases credit risk and potential loss of principal. There is no free lunch in the capital markets.

Developments in the financial markets over the past 10-15 years have given rise to more exotic, alternative asset classes which use sophisticated strategies to either improve returns, generate extra current income, or dampen volatility. Examples include hedge funds, distressed debt, and private equity funds. We do not recommend that novice investors employ such strategies.

Insurance products are sometimes marketed as investment vehicles. We believe that insurance intended to protect against a specific risk of loss is appropriate under the right circumstances (e.g., life insurance in case of death). We do not, however, recommend purchasing insurance products as saving/investment vehicles due to their complexity and cost.

When it comes to selecting the actual securities that you will own in your portfolio, you can either purchase individual stocks and bonds or invest in actively or passively managed funds, such as mutual funds or exchange traded funds (ETFs).

Today, ETFs seem to be the investment vehicle of choice due to their lower cost structure, intra-day pricing, and efficient taxation as compared to mutual funds. Mutual funds and ETFs also quickly and efficiently expose the investor to a broad basket of securities, and are appropriate for smaller portfolios. Typically, though, it is cheaper to own individual securities than it is to own a fund. Owning individual securities also offers more flexibility when managing capital gains and losses.

Depending on the source of your savings, you may hold your funds in taxable, tax-deferred, or non-taxable accounts.

Taxable accounts are a good place to hold emergency reserves and savings in excess of retirement contributions because there’s no penalty for withdrawals. You should seek to fully fund your retirement account before using this account type for retirement savings.

Tax-deferred accounts such as traditional IRAs, 401(k)s, and 403(b)s are the most common types of retirement accounts, with no taxes due until funds are withdrawn in retirement.

Non-taxable accounts (Roth IRAs) are a bit different in that after-tax dollars are used to fund the account, no taxes are due on income while in the account, and withdrawals are not subject to taxation.

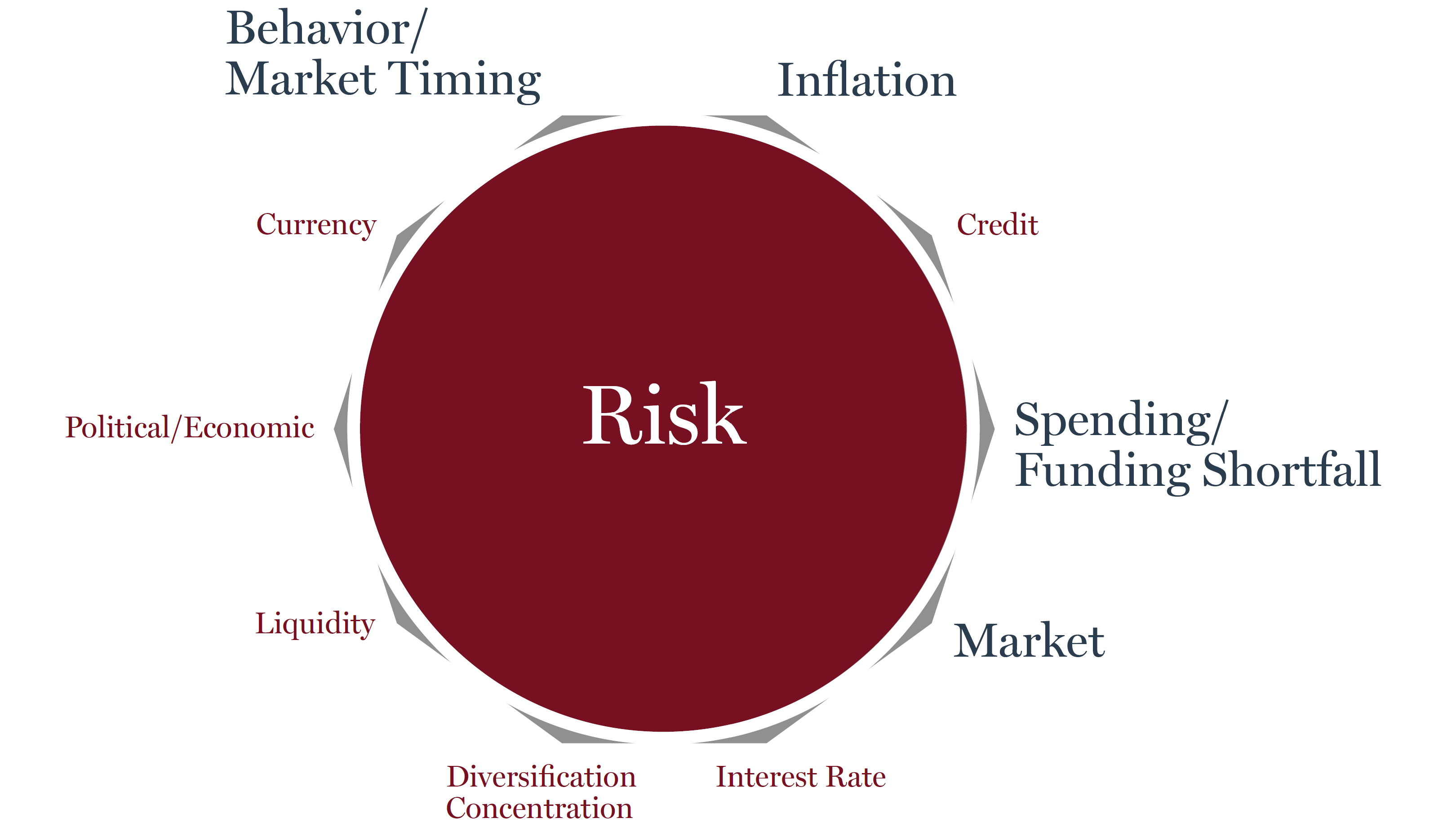

It’s important to understand the different financial risks you face when investing; and if you follow the news, you’re probably well aware of short-term swings in market prices. Market volatility may cause anxiety, but it rarely results in permanent financial loss, especially if you have constructed and diversified your portfolio well. While volatility is often portrayed as the greatest risk to savings, the actual risk of it having a long-term adverse impact on your savings decreases significantly with time. In fact, in the hierarchy of investment risks, volatility isn’t even near the top. Investor behavior (trying to time the market), inflation, and excessive spending all pose larger threats to your savings goals. Our planning note, ‘Three Investor Behaviors that Mitigate Risk’ offers a more complete discussion on this topic.

Bearing all of this in mind, we still know that saving can be overwhelming and financial markets can seem confusing. But by breaking down the saving and investing process, it becomes more manageable. It’s all just a matter of identifying your specific goals, determining the right savings rate, aligning your time horizon with your investment choices, and balancing financial risks. There are very few guarantees in life; but with planning, patience, and a properly structured portfolio, you can greatly increase your chances of success.

An update on the second round of sweeping legislative reforms